It was 40 Thanksgivings ago that two well-meaning teenagers in the western

Massachusetts town of Stockbridge found themselves on the wrong side of the

law, embroiled in what would become perhaps the most notorious episode of

littering since the Boston Tea Party.

It was 40 Thanksgivings ago that two well-meaning teenagers in the western

Massachusetts town of Stockbridge found themselves on the wrong side of the

law, embroiled in what would become perhaps the most notorious episode of

littering since the Boston Tea Party.

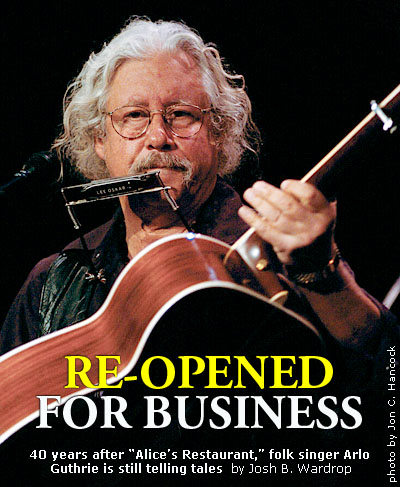

One of those teenagers was Arlo Guthrie-son of folk music legend Woody Guthrie-and it was he who turned a tale of two hippies' harassment by local authority figures into a sprawling, hilarious indictment of the American government and the escalating conflict in Vietnam. Released in 1967, Guthrie's song, "Alice's Restaurant," became one of the first socially conscious protest records.

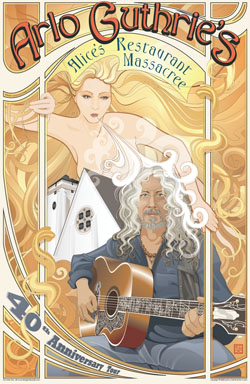

The song eventually spawned a feature film of the same name, became a Thanksgiving Day tradition on radio stations throughout Massachusetts (where Guthrie resides to this day) and made Woody's son a recognized singer-songwriter in his own right. Now, 40 years after "Officer Obie" dragged Arlo to jail for littering, Guthrie is out on the road for the Alice's Restaurant 40th Anniversary Massacree Tour, which comes to Symphony Hall on November 16 .

"I didn't think I'd be playing it 10 years later, never mind 40 years," says Guthrie, of the song considered his magnum opus. "It's bittersweet in a way, because these days I love the familiarity and the nostalgia some people get from it. But that era in the '60s-the response that came from an audience of that time who'd never heard it-that's a once-in-a-lifetime thing."

According to Guthrie, bringing "Alice" out of mothballs this year was a no-brainer, not only because of the 40th anniversary of the inspiring incident but because of what he considers a similar national mindset to that of four decades ago. "We have a country that's pretty divided, we're fighting an unpopular war overseas, and we've got all these fairly wacky politicians in office," Guthrie chuckles. "This is very familiar to people who lived through the '60s."

One might think that a musician like Guthrie, who has spent so much of his

musical career trying to make the world a better place through social activism,

would be discouraged that the dissatisfaction in America today hasn't led to a

rebirth of protest music in the mainstream. Instead, Guthrie looks at it from a

positive perspective.

One might think that a musician like Guthrie, who has spent so much of his

musical career trying to make the world a better place through social activism,

would be discouraged that the dissatisfaction in America today hasn't led to a

rebirth of protest music in the mainstream. Instead, Guthrie looks at it from a

positive perspective.

"Obviously, the mainstream music scene has been overtaken by corporate types for whom political dissent isn't in their best financial interest," says Guthrie. "But there are so many more outlets now than the major record labels, so the artists can leave the industry and do it themselves.

"You may not believe it, but [socially-conscious performers] are a lot easier to find these days," he continues. "There's the Internet, independent record labels.and all the folk festivals are full. They're booming."

Guthrie laughs, and adds, "It's like my old friend [musician] Tom Paxton says: 'People won't believe it, but there's hundreds of dollars to be made in folk music!'"

"Alice" had been retired from Guthrie's act for roughly 10 years before this tour. The singer says that he now only brings out the tune-which was around 18 minutes when recorded and has reached an unwieldy half-hour or longer in concert-for special occasions.

"I stopped doing it in 1972, when the draft ended, then I brought it back when Carter was in office, and since then it's mostly been during the anniversaries," he says. "When the song got to the point where I'd be singing it and thinking about what was for dinner, I figured it was time to drop it. Nobody wants to be a trained seal act, doing the same tricks over and over-now, it's been 10 years, the song's not rote to me, and I really look forward to singing it again."

Once the first leg of the 40th anniversary tour wraps up in December, Guthrie

plans to move on to an endeavor tied to another of his classic recordings.

Beginning December 5, Guthrie and some of his musician friends and family will

be riding Amtrak's "City of New Orleans" line from Chicago to New Orleans,

stopping along the way to perform shows at train stations and small venues.

While touring, Guthrie plans to collect musical gear-instruments, sound and

lighting equipment, microphones and so on-to donate to an integral New Orleans

community devastated by Hurricane Katrina: musicians and club owners who lost

everything.

Once the first leg of the 40th anniversary tour wraps up in December, Guthrie

plans to move on to an endeavor tied to another of his classic recordings.

Beginning December 5, Guthrie and some of his musician friends and family will

be riding Amtrak's "City of New Orleans" line from Chicago to New Orleans,

stopping along the way to perform shows at train stations and small venues.

While touring, Guthrie plans to collect musical gear-instruments, sound and

lighting equipment, microphones and so on-to donate to an integral New Orleans

community devastated by Hurricane Katrina: musicians and club owners who lost

everything.

"[After the disaster] I was watching the news, and trying to think what else I could do to help besides send money to the Red Cross," Guthrie recalls. "And I thought about all the musicians that live down there. All kinds of help is coming to people down there, but if everybody does the same thing then there's a lot that doesn't get done. We wanted to focus on the music."

Ironically, just weeks before Katrina struck, Guthrie (who recorded what many consider to be the definitive version of Steve Goodman's song "City of New Orleans" back in 1972) had been lobbying Congress to continue funding for the "City of New Orleans" line-one of Amtrak's major routes, which was in danger of being shut down. After the hurricane, Guthrie approached Amtrak about teaming up for a charity mission both symbolic and grounded in history.

"Amtrak got excited about it, and I sent out, literally, three or four e-mails to friends asking whether they'd help," says Guthrie. "And, somehow, within an hour, I'd heard back from Richard Pryor-who I've never met-and then from Willie Nelson. And it just mushroomed into an explosion of offers to help."

Guthrie hopes his efforts will help the musicians of New Orleans do their part to heal New Orleans and restore song to one of the nation's most renowned music cities. "I had a house destroyed by a hurricane, and I know what it's like to wait for help [from the government] only to realize it's not coming.and the people living with that hope in New Orleans are far worse off than I was. So, we all got to help-and someday, that goodwill will come back around when we all need it. That's how America works best."

back to homepage