IMAGINE

YES YOKO ONO at the M.I.T. List Visual Arts Center surveys the artist’s pioneering and diverse body of work

by Christopher Wallenberg

She was dismissed as the “dragon lady” and vilified for allegedly causing the breakup of the Beatles. Like

George and Ringo, Yoko Ono has always toiled in the shadow of the great, beloved John Lennon. But long

before she made waves as the wife of Lennon, Ono loomed large on her own as a pioneering figure in the

international art world, influencing, inspiring and originating many forms of avant garde art, film and

music. Now, Ono is finally getting her due with the landmark retrospective YES YOKO ONO, a survey of her

prolific, 40-year career that’s installed at M.I.T.’s List Visual Arts Center through January 6.

The traveling exhibit, billed as the first comprehensive re-evaluation of Ono’s art, is in the

midst of a six-city tour after debuting at the Japan Society Gallery in New York last year. Its

timing—only a month after the September 11 terrorist attacks—is strangely prescient, as Ono and

Lennon were perhaps the most prominent figures in the international peace movement to end the

Vietnam War.

The exhibit boasts almost 150 works from throughout Ono’s life, spanning from her early years at

the center of the avant garde Fluxus movement in the early 1960s, to the top of the pop charts

and forefront of the peace protests, to her Bronze Age transformation in the 1980s. Her art has

always been interactive, enlisting and cajoling the viewer into the creative process. Influenced

by the Dadaist doctrine championed by Marcel Duchamp and John Cage, Ono sought to find beauty and

art in the things around her. “Yoko doesn’t want to put her art on a pedestal. She tries to put

art into everyday life,” observes exhibit curator Alexandra Munroe, director of the Japan Society

Gallery.

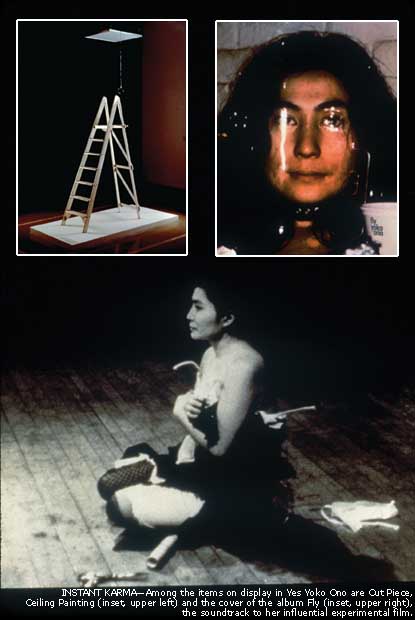

Highlights of the retrospective include: Ono’s seminal contributions to what later came to be

known as conceptual art, such as Grapefruit, the anthology of her famous “instruction” paintings;

Ceiling Painting, the piece that first attracted Lennon at her historic 1966 Indica Gallery show

in London; the classic experimental film Fly No. 13; and Cut Piece, her watershed performance work

in which she sits motionless on a stage as members of the audience are invited, one by one, to cut

off a piece of her clothing until she is left nearly naked by the end.

Yes Yoko Ono culminates with the mesmerizing A-Maze, a clear plexiglass maze that functions as a

sort of Hall of Mirrors. It was designed and constructed for Ono’s 1971 exhibition at the Everson

Museum in Syracuse, N.Y. The piece triggers visitors to think about the dichotomy between

perception and reality. For many, though, it’s simply fun trying to navigate to the end without

bumping into the transparent walls.

When Munroe ventured to ground zero in Lower Manhattan a few days after the terrorist attacks, she

stumbled upon a tree that had been festooned with hundreds of “wishes” that passersby had scrawled

out following the tragedy. Munroe couldn’t help but notice how this spontaneous memorial mirrored

Ono and Lennon’s own anti-war activism and their organized acts of “wishing” for peace during the

height of the Vietnam War.

At the press conference to kick off the exhibit, Ono spoke of her hopeful ethos in light of the

post-September 11 zeitgeist, “If we are drowning, the only way to survive is to try to come out

of the water together. Positive thinking is something we need. It’s not being naive, it’s

simply practical.”

back to homepage