Panorama gives you the inside scoop behind (and underneath) Boston's Big Dig

by Christopher Wallenberg

Boston's nightmarish traffic problem is the stuff of legend. Trying to weave your way through the city's narrow, cow

path-configured streets can be like trying to navigate the lines at the Registry of Motor Vehicles. In fact, we've often blamed our reputation for bad drivers on the city's illogical street patterns.

Boston's nightmarish traffic problem is the stuff of legend. Trying to weave your way through the city's narrow, cow

path-configured streets can be like trying to navigate the lines at the Registry of Motor Vehicles. In fact, we've often blamed our reputation for bad drivers on the city's illogical street patterns.

However, help is on the way in the form of the Big Dig. Even if you're not from New England, you've undoubtedly heard about the massive highway construction project, officially dubbed the Central Artery/Tunnel Project. It's the biggest, most complex, technologically challenging and expensive construction job in the history of the United States. It involves digging a gigantic hole through the middle of downtown Boston while keeping one of America's most historic and densely-built cities functioning around it. The scope and scale of the Big Dig puts in on par with construction of such engineering behemoths as the Panama Canal, the Chunnel under the English Channel, and the Trans-Alaska Oil Pipeline.

So what is the Big Dig, exactly? There are several portions to the project. The main segment will replace the creaky, old elevated Central Artery (I-93) that snakes through downtown Boston with a modern eight-to-ten lane highway that is being built almost completely underground. The old highway was designed to carry 75,000 cars a day when it opened in 1959 and was supposed to be for local traffic only. Not long after, however, the Federal government tied Interstate 93 into the Central Artery. The result: traffic is now clogged on the Artery 6-8 hours every day, with some 200,000 cars crawling along the hulking green highway daily.

The second portion of the project will extend the Massachusetts Turnpike (I-90) to Logan Airport through South Boston and the new Ted Williams Tunnel (completed in 1995). In addition, a breathtaking new cable-stayed bridge is being constructed across the Charles River, the widest bridge of its kind ever built. In all, the Big Dig will encompass 161 lane miles of urban highway-about half underground-in a 7.5 mile corridor. Perhaps the greatest challenge of the project is that all this construction is taking place while one of America's oldest and most historic cities continues to go about its day-to-day business. Says Central Artery/Tunnel Project Chairman Andrew S. Natsios, "We are building this new underground system of tunnels to alleviate traffic congestion, reconnect neighborhoods heretofore separated by the elevated monstrosity, create more than 100 acres of new parks and open space, improve the air quality and make the most historic city in America the most modern and the most beautiful.

Bureaucratic Boondoggle or City Savior?

Bureaucratic Boondoggle or City Savior?

The very words "Big Dig" can strike fear and outrage into the hearts of many drivers, business owners, tourism authorities and public officials in Boston. The project has been plagued by several scandals, including last year's much-publicized imbroglio over cost overruns (the final price tag had ballooned from $10.5 billion to $15 billion) that resulted in the firing of former Big Dig chief James Kerisiotes. And to many people, the Big Dig means one thing: a major public pork barrel project for the state where pork barrel spending was made famous. Despite some of the negative publicity associated with the Big Dig-the traffic congestion, the confusing, ever-changing downtown streets-when it's completed in 2004, we've been assured that all the headaches the project has induced will be well worth the wait, as its slogan proclaims.

Here's why: By 2010, the new underground highway will carry 245,000 cars per day and cut two hours off each rush hour. If nothing had been done, by 2010 the highway would be jammed with stop-and-go traffic for 16 hours each day, wreaking havoc with the regional economy. Right now, both local and interstate traffic are routed onto the Central Artery, causing bottlenecks and grinding rush hour traffic to a near halt. Instead, the newly-designed system will efficiently connect the major highways to surface streets. For example, there will be 14 on- and off-ramps downtown, almost half the number on the current highway.

The Big Dig will bring one of America's grand old cities into the 21st century. Because it will keep traffic moving, carbon monoxide levels will be reduced by some 12 percent; neighborhoods like the North End and downtown will be reconnected after being cut off from one another when the current highway was put up in the 1950s; a new, well-planned network of surface streets will be created; a morass of gas, electric, sewer, water and other utilities have already been relocated and streamlined into a grid system; and 5,000 miles of fiber optic cable and 200,000 miles of copper telephone cable will be installed. Most important, however, is the open space component. Some 27 acres of parkland will sprout up when the dilapidated old highway is torn down. Plans for this space are still being formulated, but it will include parks, fountains, trees, a year-round botanical garden and some moderate-sized development.

Engineering Marvels

Engineering Marvels

Whatever you say about the Big Dig, there's no denying that it's a triumph of human ingenuity. The project features the largest use of "slurry wall" construction anywhere in North America. The slurry walls, the backbone of the project, are concrete walls that run from the surface of the ground down to bedrock. The walls form the borderline of the area that's going to be excavated for the underground highway and will eventually form the walls of the new Central Artery. They make construction of the new highway possible within the tight confines of old Boston. They also allow the city to remain open for business because they keep surface traffic moving along the decking overlaid on top of them, and they hold the old elevated highway aloft as construction proceeds below.

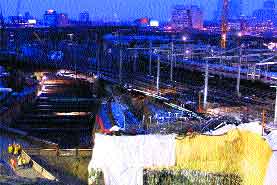

The Big Dig's other major engineering marvel is the first utilization of jacked vehicle tunnels in North America and one of the largest uses of this technology ever attempted in the world. The "tunnel jacking" for the Big Dig is being carried out where the extension of I-90 passes under the train tracks near South Station. The tunnel sections, which were first built in a jacking pit, weigh approximately 20,000-35,000 tons each. In order to prevent the tracks from caving in or disrupting train service, the ground is frozen by implanting approximately 2,400 circulatory pipes into the earth and then channeling a sub-zero calcium chloride solution into them. "The frozen ground gives us the necessary stability to mine ahead of the tunnel sections that we are hydraulically jacking forward, a few feet each day, without risking the settlement, or worse, the collapse, of the railroad tracks above," explains chairman Natsios. Another portion of the project where technology seems to trump the impossible is at Fort Point Channel, where giant, concrete tunnel tubes (weighing as much as a Navy battleship) are being built and then immersed onto the bottom of the channel. Another tricky spot is at South Station, where the northbound section of the highway passes within inches of the Red Line tracks above, which themselves run immediately below the new Silver Line station that's under construction.

Yet the project's most visible achievement (to the public, at least) is the 10-lane Leonard P. Zakim Bunker Hill Bridge, whose gleaming white cables form two triangles that resemble the billowing sails of a clipper ship. This cable-stayed wonder, which spans the Charles River, will be the widest bridge of its kind in the world when it opens to traffic in 2002. Two lanes will be cantilevered off to one side, making it the only cable-stayed bridge on the planet with an asymmetrical design. Created by Swiss architect Christian Menn, the bridge boasts two 270-foot

inverted Y-shaped towers made to echo the nearby Bunker Hill Monument. More than halfway complete, the 1,457-foot span is already making waves, and many are predicting it will become a landmark that will rival the State House and Faneuil Hall as Boston's most

recognizable.

Yet the project's most visible achievement (to the public, at least) is the 10-lane Leonard P. Zakim Bunker Hill Bridge, whose gleaming white cables form two triangles that resemble the billowing sails of a clipper ship. This cable-stayed wonder, which spans the Charles River, will be the widest bridge of its kind in the world when it opens to traffic in 2002. Two lanes will be cantilevered off to one side, making it the only cable-stayed bridge on the planet with an asymmetrical design. Created by Swiss architect Christian Menn, the bridge boasts two 270-foot

inverted Y-shaped towers made to echo the nearby Bunker Hill Monument. More than halfway complete, the 1,457-foot span is already making waves, and many are predicting it will become a landmark that will rival the State House and Faneuil Hall as Boston's most

recognizable.

That's a Fact

With a project of this magnitude, the folks at Big Dig headquarters have compiled a list of facts and figures that help illustrate the sheer magnitude of this project. Here are a few of the more illuminating chestnuts culled from the Big Dig website (www.bigdig.com).

The End of the Road

The Central Artery/Tunnel Project is scheduled for completion in several stages: In June 2002, the I-90 extension through South Boston to the Ted Williams Tunnel will open to traffic. The northbound lanes of the Central Artery will start carrying vehicles in November of 2002, with the southbound lanes unveiled in November of the following year. The project will be fully finished by the end of 2004, signaled by the dismantling of the old,

elevated highway. So as we countdown the final four years of the Big Dig, there's no denying that the city is being reshaped for the 21st century. And after all the construction is complete, our notoriously bad drivers may have no more excuses left. For more information on the Central Artery/ Tunnel Project, visit

www.bigdig.com.

back to homepage