Mountain Man

Filmmaker

David Breashears scaled Africa’s highest peak to capture his

latest IMAX endeavor, Kilimanjaro

Filmmaker

David Breashears scaled Africa’s highest peak to capture his

latest IMAX endeavor, Kilimanjaro

by Andrew King

He is the voice of calm control, even though things are not going as planned. This can happen in his business, and he handles the “hiccup” with commanding grace. This time, however, mountaineer/filmmaker David Breashears is not reporting live via radio from the summit of Mount Everest—as he was the first ever to do in 1983—but instead from a telephone in a New York City hotel room. He’s coping with a fortuitous power outage that has foiled the world-premiere viewing of his latest IMAX film Kilimanjaro: To the Roof of Africa, which has just had its New England debut at the Museum of Science’s Mugar Omni Theater. But for a man who’s spent most of his life dangling from ropes and scaling rock faces on the slopes of the world’s most treacherous mountains, this is no big deal.

Breashears, who lives in the Boston area (on the rare occasion he’s not travelling), became entranced by mountains as a kid growing up in the Rockies. “I heard tales that people climbed those things,” he says. And by the time he saw a picture of Nepalese legend Tenzing Norgay on the summit of Mount Everest, he decided to dedicate his life to climbing. It was “accidental” that Breashears ever got into film—a result of many apprenticeships under climbers who were experimenting with adventure film. Eventually, Breashears took control of the camera himself and became the leader in his field.

Anticipation for Kilimanjaro has been high, considering Breashears’ celebrity status following his 1998 film Everest, which is by far the most successful IMAX movie ever made—an unprecedented, spectacular panoramic account of the world’s loftiest peak. But the filming of Everest also became poignant for reasons that no one ever wished for or could have expected.

The 1996 expedition coincided with a tragedy that, because of bad weather, poor planning and overcrowding, left eight climbers dead. Breashears and his crew were not among those in danger, but when they learned of the unfolding disaster, they put down their cameras and began saving lives. The film, along with Jon Krakauer’s best-selling book Into Thin Air, attracted the attention of the world, and raised important questions about the commercialization of Everest.

A couple of years later, Breashears reached the summit of Everest for the fourth time, on this occasion to film an investigative documentary for NOVA examining the effects of high-altitude and, specifically, the hypoxic mental state that may have contributed to the poor decision-making on that fateful day in ’96.

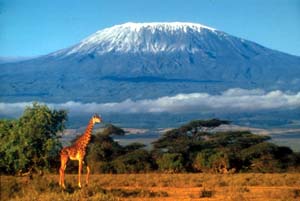

SLEEPING GIANT—The solitary Mount Kilimanjaro, the largest mountain in Africa, reveals its paradoxical, equatorial snowcap from the Tanzanian savannah. |

Kilimanjaro has no such implications. It explores the mystical allure of Africa’s greatest mountain, through the oscillating lens of Breashears’ large-format camera and through the voices of a diverse crew of climbers ranging ages 12 to 64. “With Kilimanjaro, we started out with the idea of the mountain, its climate zones and its rich geologic history,” he says, referring to the five distinct regions the climbers passed through on their way to the top. Viewers at the Omni Theater behold climbers who seem to be on several distinct journeys: a tropical excursion; a walk among other-worldly, “Dr. Seuss”-like vegetation; an African safari; and finally, a deep-blue arctic glacial mass. Along the way, they confront elephants, elands, duikers and other wildlife, not to mention the odd and brilliantly colorful plants that grow on the mountain’s lower climates.

Breashears refers to Kilimanjaro, simply, as “a solitary giant on the East African plain.” In fact, Mount Kilimanjaro is the largest free-standing mountain in the world—rising 19,340 feet above sea level into a volcano-shaped, snow-dusted giant residing over the Tanzanian landscape. Its western summit, Masai (Ngaje Ngai), means “the House of God.”

From ancient African lore to Ernest Hemingway’s “The Snows of

Kilimanjaro,” this majestic peak has inspired metaphor and

mysticism across generations. “I think the reason Kilimanjaro has

such a prominence in our imaginations is that it is a paradox—a

snow-capped mountain at the equator—and it is solitary. It just

comes down and sits there so big and so heavy and so broad, it

bends the Earth’s crust beneath it,” says Breashears.

But as awe-inspiring as its forests, Martian-like traverses,

ice-clung peaks and sheer size appear in the film, Breashears

says his work reveals as much about human wonder as it does the

landscape. “The wonderful thing about the climb of a mountain is

it has a really clear narrative: you start, you go to the top,

you come down…That’s how I work as a filmmaker—to have some

structure. Here is the story that can come out of the natural

history of the mountain, here are the people who can tell us

those stories.”

THE HIGH DESERT—The crew of Kilimanjaro sets up camp at the mountain’s fourth zone, a dry, desolate span of rocks and dust. |

Those people include a winsome 12-year-old from Massachusetts, Nicole Wineland-Thomson; Heidi Albertsen, 23, a Danish model and artist; Roger Bilham, 55, an earthquake and volcano expert from the University of Colorado; Hans “Hansi” Mmari, 13, who grew up just miles from Kilimanjaro; Audrey Salkeld, 64, an award-winning author and historian who has worked with Breashears in the past; and Jacob Kyungai, 50, an accomplished Chagga mountain guide who’s climbed Kilimanjaro over 250 times.

Because there is no narrator, it is the voices of the characters, Breashears says, that guide the film. Call it cinema verite for adventure movies. These different voices form a mosaic of perspectives that give nearly everyone in the audience a vicarious opportunity to relate to the film. “They all had to bring a dimension of the experience to life so that it was not repetitive.”

He explains that with 12-year-old Wineland-Thomson, for instance, we get a child’s observations of plants and animals, and what she finds daunting about the whole experience. And with Salkeld, who has written a book to accompany the film, Breashears says he wanted “clear, calculated thoughts on what it meant to be 64 years old, climbing a big mountain for the first time…and as a botanist, I knew she could comment beautifully on the fauna as well.” The same goes for the others, each playing his or her own role in a real-life narrative that uses one of the world’s most beautiful mountains as its stage.

What’s next in Mr. Breashears’ ever-adventurous personal

narrative? “I am very much enjoying promoting the film and

thinking of returning to smaller projects where the camera fits

in the bottom of your pack and your team is just a few friends

out doing something.”

back to homepage