Misplaced

within the annals of history, a major Thai dynasty makes a

modern-day reemergence at the Peabody Essex Museum

Misplaced

within the annals of history, a major Thai dynasty makes a

modern-day reemergence at the Peabody Essex MuseumHistorians and criminals wouldn’t seem to inhabit much common ground. But those who study extinct cultures have had occasion throughout the years to be indebted to scavengers and grave-robbers.

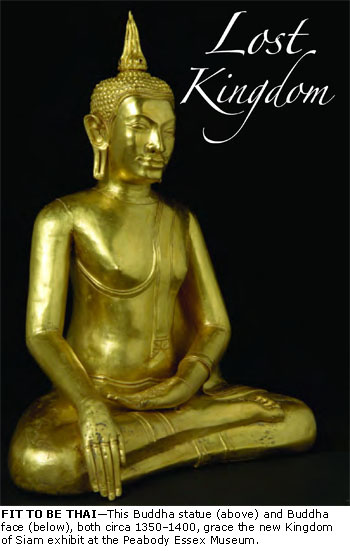

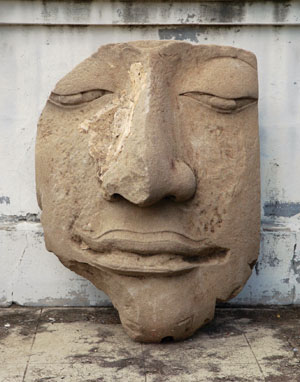

An example of this serendipitous intersection of archaeology and larceny sees the light of day at Salem’s Peabody Essex Museum this month with the opening of The Kingdom of Siam: The Art of Central Thailand, 1350–1800, an exhibition that introduces the lost Thai kingdom of Ayutthaya to American art lovers.

A major Southeast Asian center of trade that once rivaled China’s Ming Dynasty for prestige, Ayutthaya fell to invading Burmese armies in 1767, and much of the civilization’s records, artwork and architecture were lost to history—that is, until the helpful intrusion of a group of thieves in 1957.

“Little was known about Ayutthaya until [the thieves] broke into a temple and discovered a large collection of art sealed in a tower,” says Susan Bean, curator of South Asian and Korean art at Peabody Essex. “At that point, scholarship began to increase and a wider appreciation developed for this lost civilization.”

Thanks to cooperation between museums in Thailand and the San Francisco Asian Art Museum, who originated the exhibit, many of those works—pieces that include bronze and ivory sculpture, lacquered furniture, manuscripts, woven cotton textiles and much more—are now on display. Bean estimates that close to 50% of the pieces have never been seen in the Western world, and Peabody Essex represents the only East Coast stop for this collection.

As Bean will attest, the works

of art a culture leaves behind often say a great deal about the

society itself. While one can only shudder to think what future

generations will think of us upon the discovery of a cache of

Ashlee Simpson CDs and old episodes of “Fear Factor,” the relics

that make up The Kingdom of Siam exhibit portray the Ayutthayans

as a people that balanced their economic prosperity with a strong

degree of spiritualism.

“Many of the works relate to the practice of Buddhism,” says Bean, “which tells us that religion was extremely important to their society.” Bean points out that a number of the pieces unearthed in the 1950s were sculptures that told stories from the life of the Buddha, and she believes that “that was how people [of the Ayutthayan civilization] learned values and morals.”

Beyond providing beautiful artifacts for the eyes to feast on, Bean hopes that The Kingdom of Siam exhibit will allow visitors to pause a moment and contemplate how fickle history can be and how the enormity of time can dwarf even the most powerful of societies.

“Really, one of the most interesting things about this exhibit is how it brings forward a civilization that truly got ‘lost’ for awhile,” says Bean. “Most of the time we don’t pay attention to the way important civilizations—centers of art, culture and trade—can just come and go, as history passes.”

The Kingdom of Siam: The Art

of Central Thailand, 1350–1800 is on display at the Peabody Essex

Museum until October 16.

back to homepage