Inside the Boston Public Library

Peek at the Past

French ventriloquist M. Nicholas Marie Alexandre Vattemare proposed the original idea of the library, according to BPL employee Rosemary Lavery. “He conceived the idea of an exchange of books and prints between French and American libraries,” she explains. Mayor Martin Brimmer accepted the 50 volumes at City Hall in 1843 that kick-started it all, making the Boston Public Library America’s first publicly supported municipal library. When it was officially founded five years later, it boasted roughly 16,000 volumes crammed into two rooms of a public school building downtown.

As the collection grew, it became clear that the library needed a space of its own. In 1895, architect Charles Follen McKim completed his self-proclaimed “palace for the people”—the McKim Building—at the present Copley Square location. In the years following, it was filled with inscriptions, sculptures and murals, rare books, manuscripts, maps and prints. At the building’s core, an open-air courtyard became home to Frederick Macmonnies’ sculpture “Bacchante and Infant Faun,” renowned French artist Pierre Puvis de Chavannes painted a series of eight murals on the walls of the grand staircase, and murals by John Singer Sargent adorn the third floor.

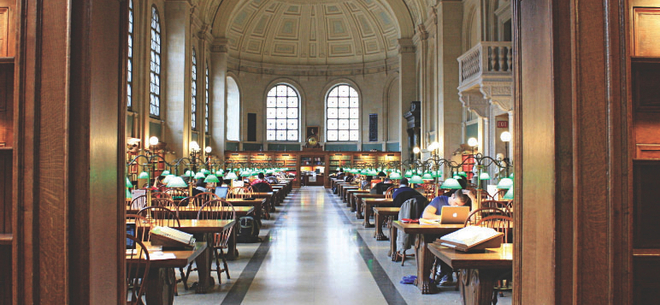

Bates Hall—one of the most architecturally revered rooms in the world—is a cavernous reading room running the length of the Copley Square façade. The barrel-arched ceiling echoes the clip of turning pages, and the walls are lined with English oak bookcases and busts of famous authors and Bostonians like James Fenimore Cooper and Mark Twain. It was named for Joshua Bates, a merchant banker and the first great benefactor to Boston Public Library. In 1952, he donated $50,000 for purchasing books, declaring, “The building shall be such as to be an ornament to the City, that there shall be a room for one hundred to one hundred and fifty persons to sit at reading tables, and that it be perfectly free to all.”

Over the years, scholars and researchers from all over the globe traveled to the BPL to take advantage of what it has to offer. The Special Collection includes 300,000 prints, drawings and postcards, one million manuscripts, and one million photographs. Some savored treasures are the first four folios of Shakespeare’s work, original music scores from Mozart and the personal library of John Adams. Special exhibitions from the collections are ongoing, including the current exhibition “Charting an Empire: The Atlantic Neptune,” a look at nautical charts, navigational instruments, and ship models dating from the 18th century (on view at the Norman B. Leventhal Map Center until November 3).

The library’s collection grew to capacity in the 1950s, and city officials called Philip Johnson to build the modernist, seven-story extension along Boylston Street, which now holds the circulating collection. The BPL is now the second largest in the United States, with 24 branches across the city and a grand collection of more than 23 million volumes.

“The Library is more than a collection of books,” Lavery says. “It is a center of knowledge, a gathering space for the community, and a free resource to all who enter its doors.” It has certainly come a long way from the idea that sparked it all 165 years ago.

Get up close and personal with the BPL at free Art & Architecture Tours Monday through Saturday. Schedule at bpl.org.